The single best thing you can do for the long term health, quality and maintainability of a non-trivial software system is to carefully manage and control the dependencies between its different elements and components by defining and enforcing an architectural blueprint over its lifetime. Unfortunately this is something that is rarely done in real projects. From assessing hundreds of software systems on three continents I know that about 90% of software systems are suffering from severe architectural erosion, i.e. there is not a lot of the original architectural structure left in them, and coupling and dependencies are totally out of control.

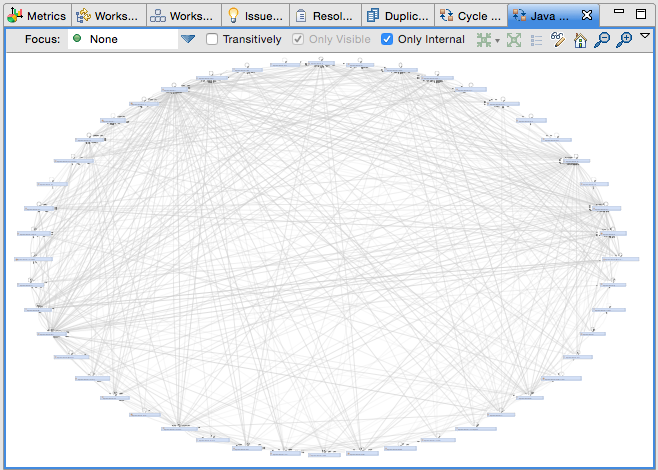

48 Packages in a cyclic dependency group (Apache Cassandra Project)

The screenshot (Sonargraph-Explorer) shows how dependencies got out of control in the Apache Cassandra project, which is still a relatively young open source project. There are 57 different packages in the project, and 48 of them are so tangled that whatever architecture might have existed in the early stages of the project is now completely unrecognizable in the code. That does not mean that Cassandra is a bad piece of software, but it definitely means that it is hard to maintain or comprehend.

One of the many reasons for this is that usually there is nobody in the development team whose role it is to keep and eye on architecture and dependencies. This is kind of ironic because there is certainly no lack of people with the title “software architect” in their job description. Another reason is that, with the wide adoption of agile development processes, architecture is more and more considered as a by-product of the implementation of user-stories. If all the focus is on “visible” features there is not a lot of capacity left to take care about invisible properties like architecture and technical quality of code.

All this leads to a growing accumulation of the most toxic form of technical debt, architectural debt, and it comes with a painfully high interest rate. The unfortunate side effect of this is that it becomes more and more difficult to add new visible features without breaking something. If you neglect dependency management long enough you will reach a point of no return. Your system will become so tangled that the effort to repair its structural deficiencies will become prohibitively expensive. Then you will have to live with the mess for the remaining lifetime of the system, which usually is not a lot of fun. The stakeholders will notice instability, high maintenance cost and ridiculously high cost for adding or changing features. The development team will be under increasingly high pressure which will further deteriorate the situation.

How to set up an architecture

Mastering the architecture of a complex software system is like ruling an empire. Divide and conquer is, therefore, an excellent strategy. To define an architecture you will have to partition your system into smaller units and then describe how these different elements can depend on each other. I will call the atomic unit of architecture a “component”. In Java a component would be a single Java file, in C++ it would be the combination of a source file and its related header file.

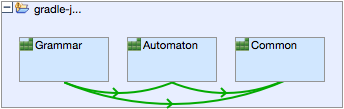

The first level of structuring components is to group related components into “packages”. Conveniently Java already offers this concept, in C++ or C# you could combine the usage of namespaces and physical directories to emulate packages. Upward from the package level, the architecture depends on the kind of system you are creating. For a classical enterprise application you will probably need layers to separate technical aspects and slices that cut through the layers to separate functionality. For other kinds of systems it might be enough to define just a couple of subsystems.

Architectural model with layers and slices

Architectural model with subsystems only

No matter what your architecture looks like, it is always a good idea to express architectural grouping in your package names. This way you will know exactly where a certain package belongs in your architecture by just looking at its name.

Possible naming conventions could be:

com.company.project.slice.layer…

com.company.project.subsystem…

For C++ or C# you can achieve the same thing by using a combination of nested directories and namespaces.

One important rule of sustainable architecture is to avoid cyclic dependencies between architectural elements. Cyclic dependencies are highly undesirable, because they:

- tangle together elements that have been intentionally separated by the architect.

- make code comprehension more difficult because elements involved in a cyclic dependency (we call this a cycle group) form an inseparable unit that can only be understood in its entirety.

- make testing more complicated because the unit to be tested is now the whole cycle group.

- make code re-use much more difficult, because the unit of re-use is now the whole cycle group.

The good news is that it is always possible to break up cyclic dependencies using simple software craftsmen techniques like adding interfaces or rearranging classes or methods. DZone’s refcard #130 describes a couple of those techniques in detail.

Unfortunately, most developers are not aware of the adverse effects of cyclic dependencies. And even if they are, it is difficult to detect cyclic dependencies without tool support. You will need tools to automatically detect architectural and structural problems early so that they can be fixed while it is still easy to fix them. More about that later.

Benefits of loving your architecture

If you consider that 70% to 80% of the total lifetime cost of a typical software system occurs during the maintenance phase, it becomes obvious that making maintainability easy will save a lot of money. Ease of maintenance is directly coupled to the architectural integrity of the system, and the amount of technical debt that has accumulated in it. By minimizing technical debt with a focus on architectural debt and by enforcing an evolving architectural blueprint over the lifetime of a system, total cost can be reduced by 25% or more.

Here are some of the benefits you get from keeping your architecture clean:

- Changes are much more local and therefore easier to implement and to test. Also the probability of regression bugs is lowered significantly because overall coupling is moderate.

- It is easier to reuse parts of the system because they are not tangled with unrelated pieces of code.

- It is easier to pass a system from a development team to a maintenance team, especially when changes can automatically be checked for architectural conformance. Also new team members need less time to become productive because the code is easier to understand.

- It becomes much easier to harden a system against security vulnerabilities. Tainted data can only enter the system over clearly defined architectural boundaries. Only those boundaries have to be checked regarding proper data validation. This benefit is becoming more and more crucial but is often overlooked.

- Changing architectures from a classical web application to web services and similar changes are easier because all the business logic is clearly separated from UI and service interfaces.

- Adding new features, fixing bugs or implementing changes will be simpler and more straight forward. That means typical dev ops metrics, like time needed to fix a bug or rollout a change, will all significantly improve.

Tips for implementing automated architecture checks

Keeping your architecture clean is easier than you think, provided you put some effort into it on a regular basis and fix violations while they are still easy to fix. The first thing you need is a packaging concept and naming strategy that reflects your architectural model. Then you must avoid cyclic dependencies between packages and make sure not to create monster packages with hundreds of components in them. This alone will make sure that it will be possible to assign your packages to higher level architectural elements like subsystems or layers without introducing cyclic dependencies on the higher levels. It is also a good idea to avoid cyclic dependencies between components whenever you can.

For Java there are free tools that automatically detect package cycles, e.g. JDepend or SonarQube. If you want more comfort and he ability to define and enforce architectural blueprints you will need a commercial tool like Sonargraph (shameless plug).

Update: Sonargraph-Architect now features a DSL (domain specific language) to describe software architecture as code. Learn more in my recent post “Designing a DSL to describe Software Architecture”.

Excellent article. The 48 packages that are tangled form the “core” architectural cornerstone and detangling them is necessary. Here are some tips to push for a concerted effort on detangling these :

1) Detangling the 48 is guaranteed to reduce code size.

2) Once you detangle the smallest cyclic dependencies (i.e. 3 packages), all subsequent detangling becomes easier.

3) I decomposed a monolith system into 3 separate code bases using just make and compile and a lot of grep to figure out or guess what the dependencies were and then apply a code style to all packages such that these dependencies did not form in the future.

Good luck.

-Chandra

Thanks for the positive feedback. If you run a graph algorithm to determine the minimum breakup set on the Cassandra code (Sonargraph-Explorer can do that as described in this article) you will find out that more than 30% of the edges need to go, and that this would affect approx. 4500 places in the code. This is certainly a huge effort. My point is that is always better to detect and fix those problems early, otherwise things might get really difficult. And doing that will require some sort of tool support. And codings conventions and styles can be very helpful to avoid those problems in the first place.